Mining, illegal or legal, is widespread throughout Amazonia, happening at both small and large scales. It is estimated that mining concessions covers 21% of the total surface of the Amazon basin. This is equivalent of imagining a territory over twice larger than Spain, predominantly formed by primary forests and innumerable freshwater streams, completely zoned for extraction – a mega-mine operating on planetary scale.

Mining blocks often overlap with demarcated and non-demarcated indigenous territories, communal lands and ecological reserves, generating conflicts over land and water with local communities. According to the project Environmental Justice Atlas, there current exists at least 56 water and land conflicts related to mining in the Amazon basin.

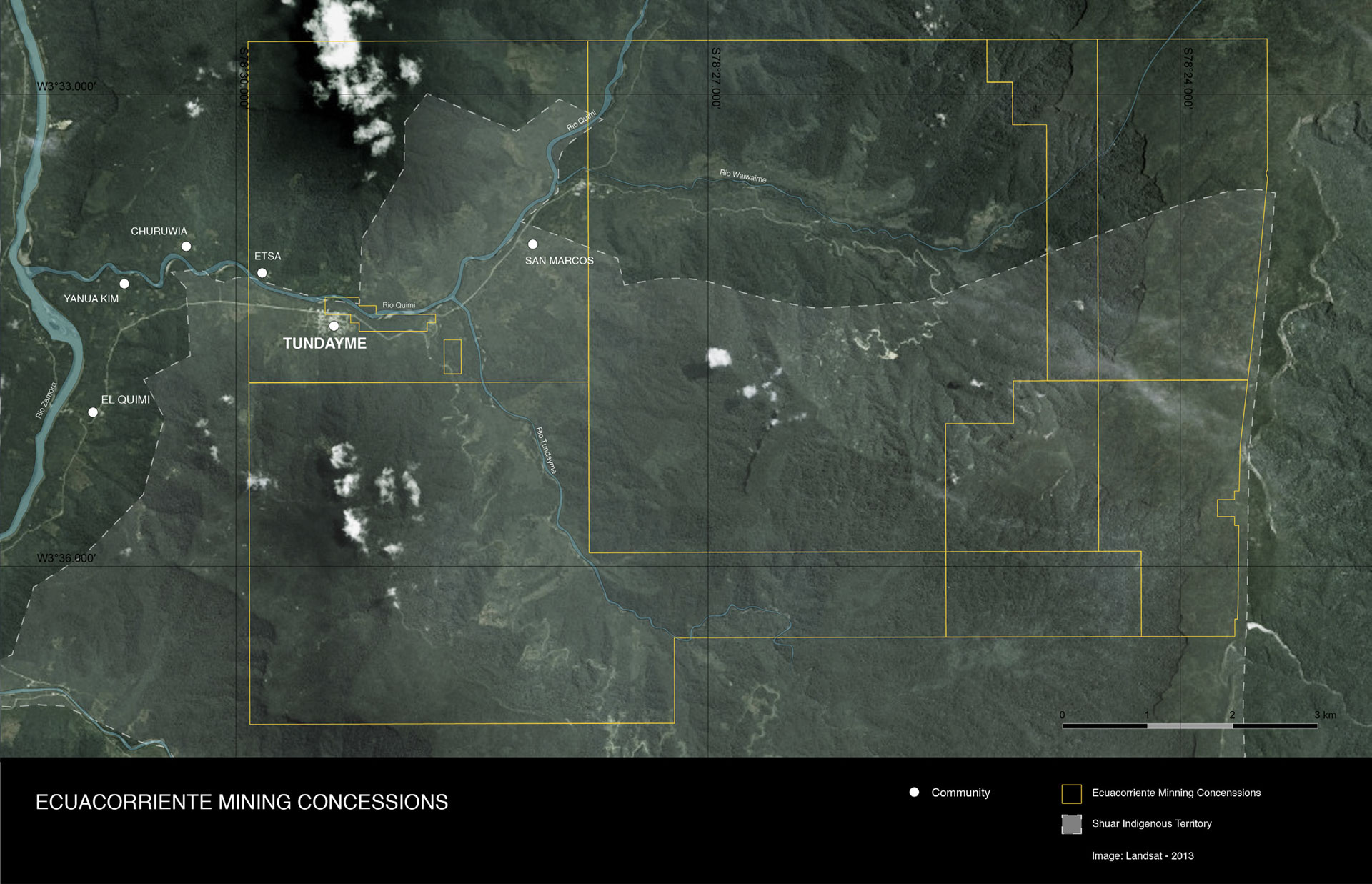

Mining concessions cover about 11% of the Ecuadorian territory. They are mainly concentrate in the southern flank of the Amazon region. These concessions are in conflict with indigenous territories and protected ecological reserves.

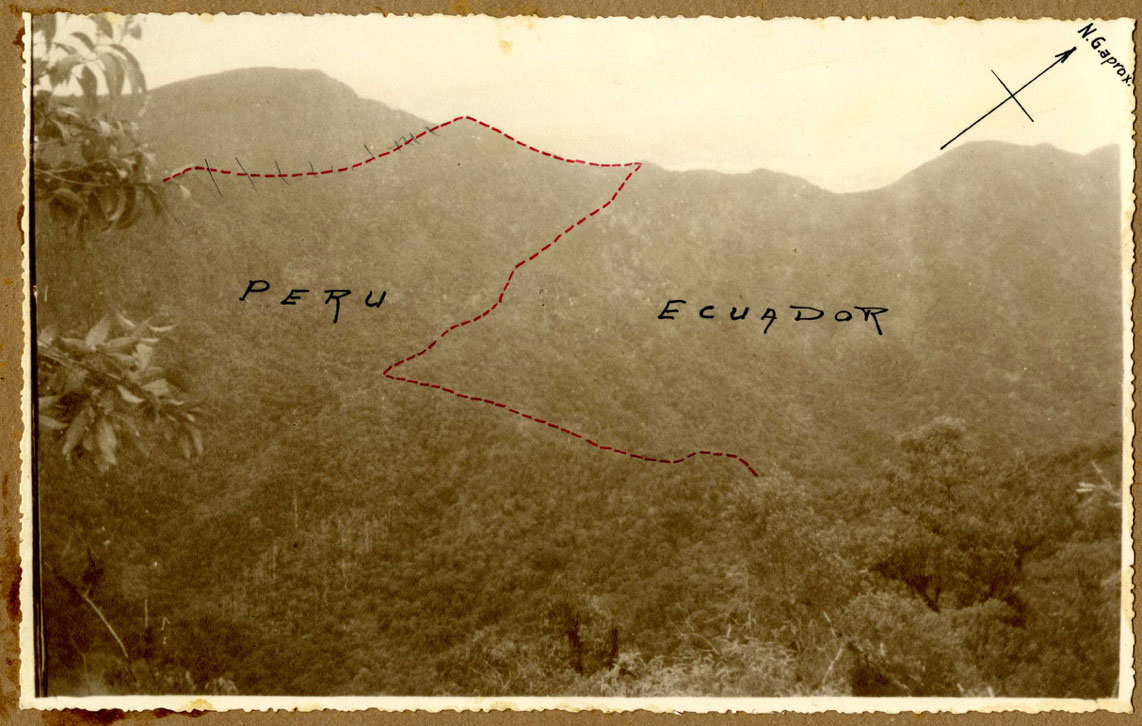

This massive push in the mining frontier in Ecuador is driven by several projects of “mega-mining.” Three ofthem – Mirador, San Carlos-Panantza, and Frutal del Norte – are situated next to each other in region of the Cordillera del Cóndor mountain range in Shuar ancestral territory, south of the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Sattelite image of the Mirador mining area in 2013, before the systematic evictions.

Location of forced evictions between 2014 and 2018 (excluding processes of "servidumbre")

Satellite image of Mirador mining area in 2019, showing the mining pit and extraction infrastructures over location of forced displacements.

The destruction of San Marcos was the first of a series of violent evictions conducted by state and private forces between 2014 and 2017, which affected at least 27 families between shuar, kichwa and mestizos throughout the region.

On 30 September 2015, at dawn and without prior notice, police officers and security guards of the company Ecuacorriente carried out an eviction against 13 families in San Marcos and on the El Cóndor road, at the margins of the Tundayme River. Equipped with guns and bulldozers, they destroyed their homes, edible gardens and hen houses, forcing elderly, women and youth to flee without place to go.

Weeks latter, on 16 December 2015, another violent land-clearing operation was conducted across the area. Once again at dawn and without prior notice and judicial order, state and private security forces and evicted more 14 families. Similar to the displacements of September, all the houses were destroyed in front of the families as a way of terrorizing them and preventing their return.

The last evictions took place on 13 May 2016 against the shuar family Tendetza-Antún in the community of Yanua Kim, and latter on 04 February 2017 against Rosario Wari and her son, by that time the last residents of the area.

This satellite image shows the site of Project Mirador in 2013, after the destruction of the village of San Marcos and prior to the forced evictions of 2014-2017. At this moment the company Ecuacorriente was initiating the construction of the extraction complex, and few infrastructural works are visible. Most of the families alongside the Tundayme and Wawayme rivers still lived in the area.

This satellite image shows the mining site in 2018, after the violent evictions of 2014-2017 that depopulated the area. The territory changed dramatically as vast tracts of forests were completely destroyed. The mine infrastructure occupies a much larger space, the tailing dams and the crater are in advanced stages of construction.

Several archaeological sites are located inside the mining concession area. The few sites that went through carbon tests show a concentration of dates between 800 and 1300 AD. According to one archaeological study, this allows to infer “a period of greater occupation” in this interval, just prior to the invasion of European colonizers. The communities that lived in this region were therefore the near ancestors of the Jivaroan peoples.

Documentation of excavation of a terrace structure st an archaeological site located where the village of San Marcos was. (site Z6DIII-04T).

Documentation of funerary urn found during the excavation of a terraza structure in archaeological site Z6C4-010

Documentation of the petroglyph found in archaeological site Z6DIII-020 before its destruction. An investigation commissioned by Ecuacorriente in 2006 identified a large petroglyph in this area. This study concludes by recommending a modification in the original project of the mine to “avoid the destruction” of the petroglyph and its adjacent archaeological structures, which included more than 30 terraced structures. These recommendations were ignored. In a field inspection conducted by the Ecuadorian National Institute of Cultural Heritage (INPC) in 2017, researchers found that the petroglyph had been “partially destroyed.”